MONASTERY

St. Benedict of Snowmass

“The Rule of Benedict

is simply an application

of the Gospel counsels

and commands of Christ

to the monastic way of life.

The observances and customs of the Cistercians seek to interpret and apply the Rule in greater detail.”

INTRODUCTION TO THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT

ST. BENEDICT OF NURSIA, acclaimed as the “Father of Western Monasticism,” was born in Italy at the end of the fifth century, and is the author of the Rule

of St. Benedict which has dominated, directed and inspired monastic life since

the time of Charlemagne. Although Pope St. Gregory the Great wrote his

biography fifty years after his death, it is in the pages of his Rule that we best

come to know the man as he describes his “school for the Lord’s service”

(Prologue, v. 45) where holiness of life may be taught and learned in religious

community.

In the composition of his Rule, Benedict relied on the work of previous monastic

writers, but in particular on the Rule of the Master, written by an anonymous

author a few decades earlier. Although the influence of the Master is evident,

particularly in the opening chapters of the Rule, Benedict locates the motive

force for monastic holiness less in the coercive external authority of the abbot

than in the individual monk’s internal submission to God’s grace.

Throughout the Rule, Benedict displays perceptive and realistic insight into

human nature, with acute understanding of its complexity of motivation and

expression. While clearly enunciating the necessity for the asceticism of

discipline and self-denial, Benedict succeeds in “setting down nothing harsh,

nothing burdensome” (Prologue, v. 46), allowing the abbot sufficient latitude

for making prudent decisions appropriate to the individual situations and

specific needs of each individual in the monastic community.

CONSISTENT with the emphasis in his Rule on the humility of mutual obedience (Chapters 5 and 7), Benedict charges the abbot with the grave responsibility “to accommodate and adapt himself to each [monk’s] character and intelligence,” keeping “in mind that he has undertaken the care for souls for whom he must give an account” (Chapter 2, vv. 32 and 34). Clearly evident is Benedict’s

conviction that it is not simply obedience to the abbot which creates holiness of

life, but the obedience and reverence of each member of the monastic

community to one another. Quoting St. Cyprian, Benedict writes: “Let them

prefer nothing whatever to Christ…..supporting with the greatest patience one

another’s weaknesses of body or behavior, and earnestly competing in

obedience to one another” (Chapter 71, vv. 5 and 11).

It is the motivation of the individual to the grace of God in living the Rule, rather

than its simple observance, that focuses Benedict’s attention. This flexibility in

the application of the sanctions of the Rule, relying on the discretion of the

abbot with allowance for weakness and failure, expresses “the spirit of

Benedict” that animates it, explaining its practical success in the guidance of

monastic life over the centuries despite the challenge of changing historical

circumstances and cultural conditions.

AS MICHAEL CASEY has observed, “The Rule of St. Benedict was never

intended as the final and definitive expression of his thought on monastic

life…..It is necessary to see it as part of an ongoing tradition” [Introducing

Benedict’s Rule, p. 18]. That tradition demands that the Rule be constantly

reinterpreted according to the time in which it is lived, recognizing that many of

the specific observances and community practices detailed within it may have

little or decreased relevance to contemporary monastic life.

To clothe the ongoing tradition of the Rule of St. Benedict with the lived

interpretation of daily monastic life is the privilege and challenge entrusted to

every Cistercian monk. As Thomas Merton defined the task, “The Rule of

Benedict is simply an application of the Gospel counsels and commands of

Christ to the monastic way of life. The observances and customs of the

Cistercians seek to interpret and apply the Rule in greater detail.” ✜

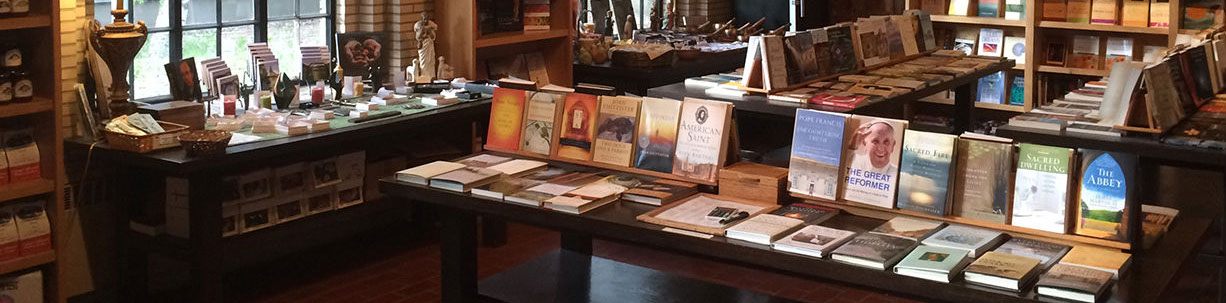

St. Benedict's Monastery | 1012 Monastery Road | Snowmass, Colorado 81654

970/279-4400 | EMAIL snowmasscoc@gmail.com